Responding to an untold history of persecution

Responding to an untold history of persecution

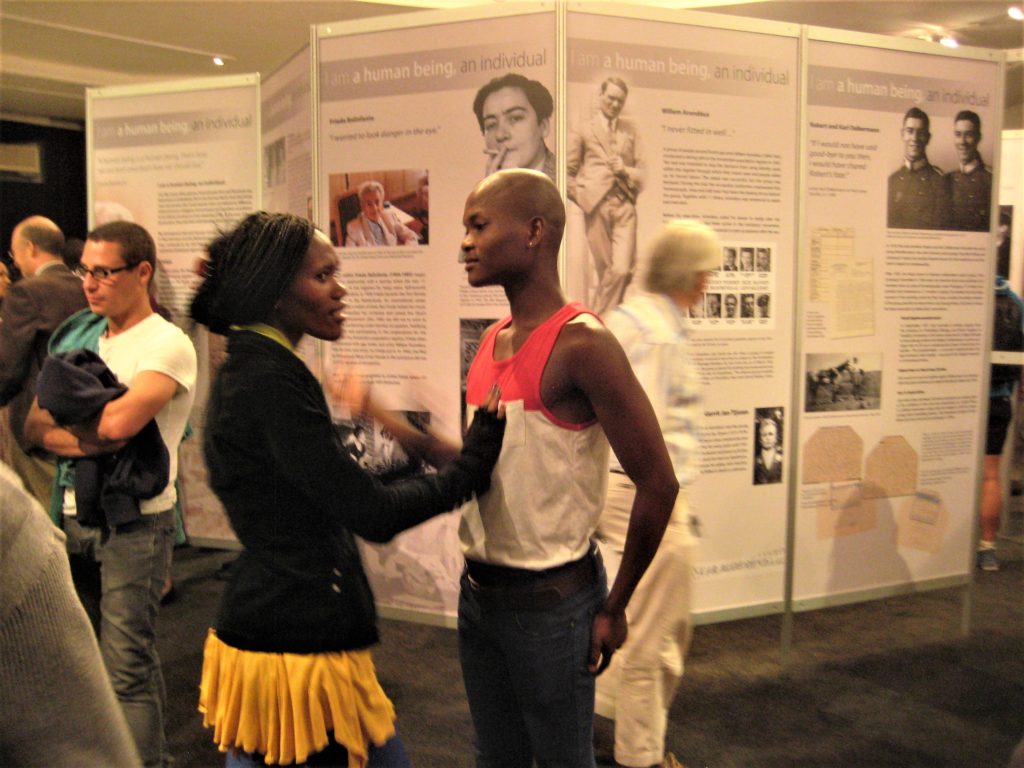

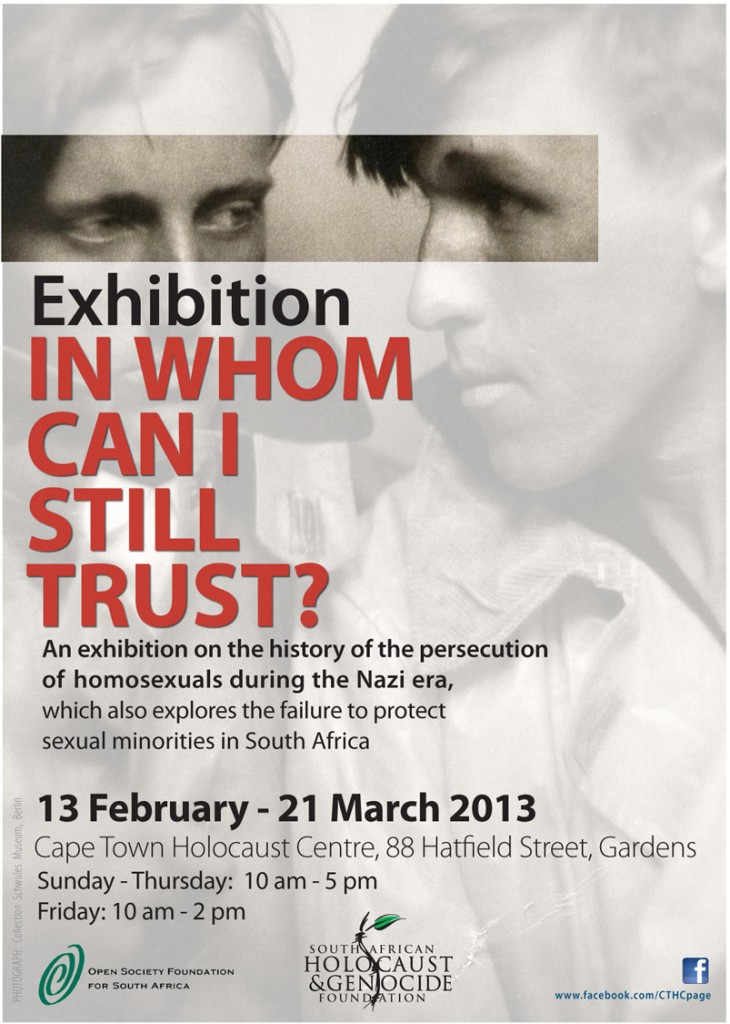

In 2013, the South African Holocaust and Genocide Foundation brought an exhibition to South Africa called: In whom can I still trust? Homosexuals in Nazi Germany and occupied Netherlands. The exhibition opened in Cape Town in February 2013 and was accompanied by public programs that included teacher workshops, panel discussions, film programs, lectures and a youth symposium.

Opening speech Cape Town REVIEWS: Daily Maverick; Cape Times

LOCATIONS 2013/14

Cape Town Holocaust Centre, Feb 12 – Mar 22, 2013 Interview Richard Freedman

Durban Holocaust Centre, Apr 17 – May 31, 2013

Bloemfontein, University of the Free State, with Institute for Reconciliation and Social Justice, Jun 6-15, 2013

Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre, Exhibit Constitutional Hill, Jul 21 – Aug 22, 2013

Baxter Theatre, Cape Town, Sep 16-20, 2013

Cape Town University, Sep 20 – Oct 15, 2013

Durban Gay & Lesbian Network, Natal Museum, Nov 5 – Dec 14

Johannesburg, Vaal University, Mar 18 – 25, 2014 (Photo gallery)

University of Pretoria, Centre for Human Rights, May 2014

The exhibition was developed by Dr. Klaus Mueller on behalf of IHLIA (Homodok/Lesbisch Archief Amsterdam) and has been shown in memorials and resistance museums in the Netherlands, including the Dutch Parliament in The Hague, between 2006-2012. The exhibition was developed in response to the largely untold history of Nazi persecution of homosexuals during the Holocaust. For its South African version, the exhibit was translated, redesigned and six panels were added on the contemporary South African context.

Historical Background – an untold history

Under Nazi rule homosexuals, men and women alike, came under pressure. State persecution – through tightened laws and special police units – focused on male homosexuality and led to the arrest of approximately 100,000 homosexual men. Lesbian women, while spared such a massive persecution, had to mask their lives once again. Personal testimonies show how individuals came under pressure in a treacherous environment.

The era of the Weimar Republic (1919-1933) had known growing tolerance for homosexuals, and a specific law, paragraph 175, that targeted male homosexuality seemed close to being abolished. In 1935, Nazi Germany tightened the old sodomy law: now the mere suspicion of homosexuality was reason for arrest. If homosexuals were charged, they could lose everything: their jobs, their homes, their honour, their freedom.

Neighbours, colleagues and passers-by in the street readily reported people in Germany. Why did so many cooperate, voluntarily reporting their friends or colleagues to the police? Were they aware of the consequences for these fellow citizens and did they not care? Homosexuals were thus forced into lying and secrecy for their own protection. They no longer knew who they could trust.

The persecution of male homosexuals in Nazi Germany was possible on such a large scale because of the ready complicity of society. In Berlin, half of the inquiries in the period 1933-1945 were the result of reports from private individuals.

After the war, gay survivors did not receive recognition as victims of the Nazi regime and post-war societies in Germany and Europe failed to show empathy for their suffering. In fact, the 1935 revised law against male homosexuality remained on the book in West Germany until 1969. Some gay survivors were re-imprisoned after their liberation and forced to serve out the remainder of their Nazi sentences. Prejudice prevailed; compensation was denied. Gay survivors remained alone and died alone with their memories; lesbian women suffered from society’s contempt and thus were forced to hide their love and relationships. Looking back at history also raises questions about the present: how strong is the recently secured position of homosexuals in society? How would family, friends or colleagues react today?

The relevance to South Africa

Despite South Africa’s Constitution and Bill of Rights, which safeguards the rights of all to be protected against discrimination on the grounds of religion, colour, creed, gender, class, ability or sexuality, homophobia and prejudice towards members of the LGBT communities remains still widespread in South African society. Attacks on lesbian women and gay men were and are frequent. School learners encounter terrible prejudice if their sexual orientation is known to be other than heterosexual. The attitude towards gay and lesbian communities in neighbouring states also is grave cause for concern: people are victimized within their societies and there are many examples of governments supporting discrimination of their gay and lesbian citizens through statutes and prosecutions. Sometimes, they even declare homosexuality to be ‘un-African’.

Statements by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on homophobic rape, however, and South Africa’s leadership on the 2011 UN resolution in which the office of United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights did draw up the first UN report on challenges faced by LGBT people worldwide, were encouraging examples of leadership on advancing LGBT equality.

The South African Holocaust and Genocide Foundation

The South African Holocaust and Genocide Foundation continues to make the exhibition accessible: please see here. The South African Holocaust and Genocide Foundation is committed, through its programmes, to use the platform of History to engage with contemporary issues. It is to this end that the Foundation hosted the exhibition and provided and provides NGOs, academics, teachers, learners and government agencies with an opportunity to discuss and raise public awareness on the issue of discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.