A Webinar with Tad Stahnke, Aleisa Fishman, and Klaus Mueller for the Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism, Indiana University Bloomington.

MUSEUMS and THE LGBTI COMMUNITY, ALMS 2019

ALMS 2019 Berlin explored the potential for generating publicities for queer archives, libraries, museums and special collections, with a special focus on the arts and artistic interventions.

I was honored to be invited to serve on its International Board and present a paper on Museums and the LGBTI Community, conduct a conversation on Archival geographies: documenting queer lives within/beyond cities, and moderate the Documentary film night.

On behalf of the Salzburg Global LGBT* Forum, Mohammad Rofiqul Islam, or Royal, showed a photo exhibit on gender diversity in Bangladesh

Archival geographies: documenting queer lives within/beyond cities

Archival geographies: documenting queer lives within/beyond cities

Chair: Klaus Mueller

Presenters:

1. Alison Oram & Matt Cook – Making Queer Place and Community: Queer Beyond London

2. Christoph Gürich & Pia Singer – ‘München sucht seine LGBTI*-Geschichte’: Munich City Museum’s Collection Appeal

3. Scott R. Cowan – Queer Roots: Preserving the LGBTQ2+ Past and Present in a Rural Ontario County

4. Beth Asbury – Out in Oxford: An LGBTQ+ Trail of the University’s Collections

5. Clara Woopen & Marek Sancho Höhne – We are here! L, G and T* Stories in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

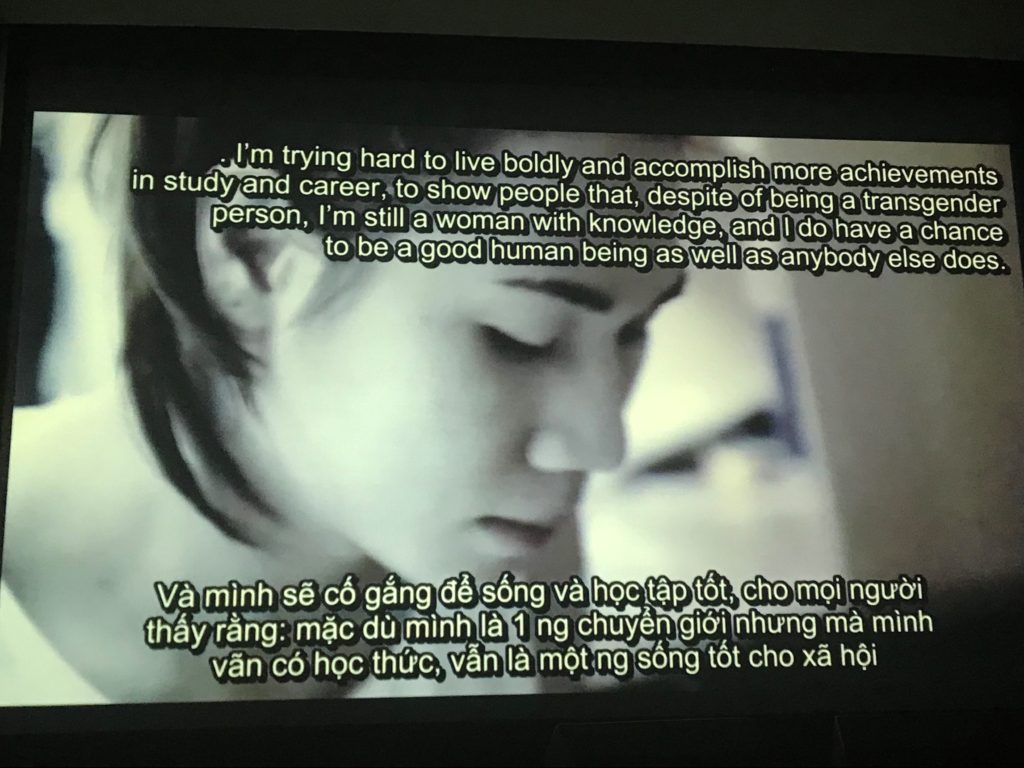

Lam by Bao-Chau Nguyen, Vietnam 2018

DOCUMENTARY FILM NIGHT

FRI 28.6.2019, 19:00–22:30@ALMS CONFERENCE, HAUS DER KULTUREN DER WELT

Chair: Klaus Mueller, Salzburg Global LGBT Forum

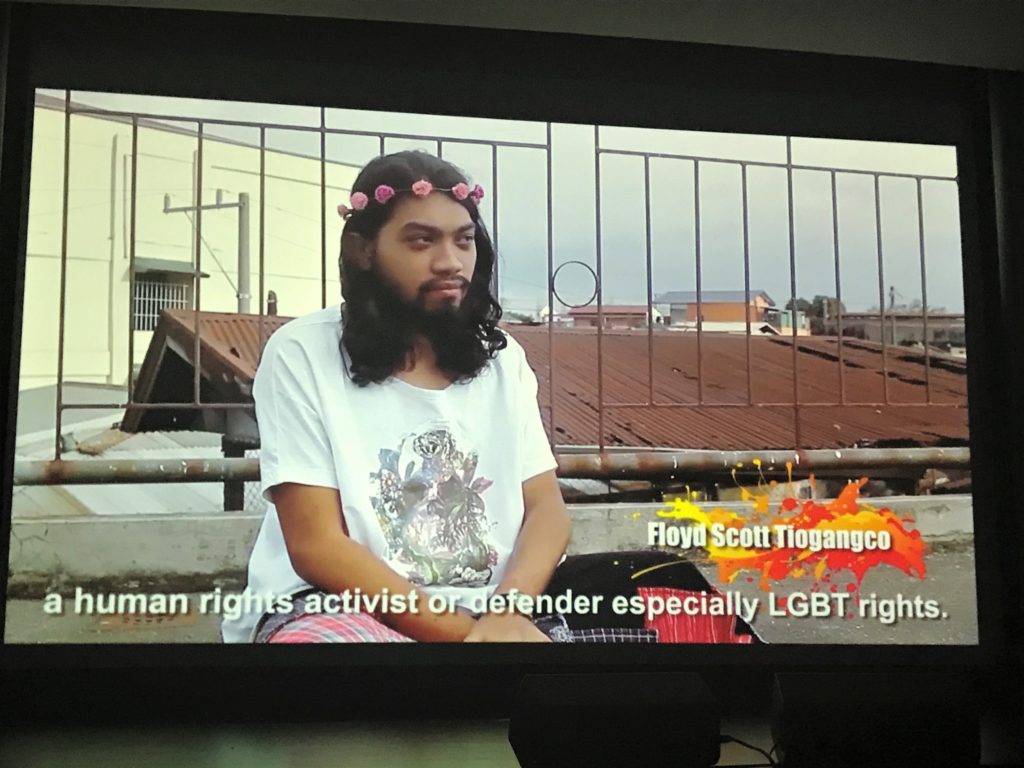

Slay by Cha Roque, Philippines 2017

SECTION 1 [65 MINS.]

Slay [Cha Roque, Philippines, 2017, 14 mins., Filipino with English subtitles]

Lam [Bao-Chau Nguyen, Vietnam, 2018, 13 mins., Vietnamese with English subtitles]

Afterimages [Karol Radziszewski, Poland, 2018, 15 mins.]

24 Hitchhikers [Paul Detwiler, USA, 2013, 5 mins.]

Family is … [Klaus Mueller, Germany, 2017, 17 mins.]

20:15–20:30 BREAK

SECTION 2 [110 MINS.]

En armé av älskande/An Army of Lovers [Ingrid Ryberg, Sweden, 2018, 72 mins.]

Die Sammlung Eberhardt Brucks: Eine Sammlung des Schwulen Museums, Berlin [Kevin Wrench & Andrew Franks, London/Berlin 2011 [English version, Berlin 2012], 20 mins.]

Blue Boy [Manuel Abramovich, Argentina/Germany, 2019, 19 mins., Winner – Silver Bear @ Berlinale]

The consolidation of European Holocaust documents in the USHMM archive (2018)

The “record of the Holocaust” has been scattered to virtually every country and is massive, reflecting the enormity of the crime and its implications. Some of this evidence is endangered, access is more often than we think a problem, and the dispersal of materials hinders expedient and productive use by researchers, survivors, and the broader public. As the distinguished scholar Professor Raul Hilberg estimated, roughly 80 percent of Holocaust records remain underutilized or unknown. Some collections – such as trial records of the perpetrators of the Holocaust – remain classified or restricted, and thus unavailable to individual researchers. Collecting, preserving, and making available evidence of the Holocaust is one of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s highest priorities.

Lecture at conference ZUGANG GESTALTEN! Mehr Verantwortung für das kulturelle Erbe (SHAPE ACCESS! More responsibility for cultural heritage) that took place under the German Unesco patronage in Berlin 2018.

Opening speech Exhibit IN WHOM CAN I STILL TRUST

Cape Town 2013

In whom can I still trust in a society that considers me inferior and dangerous?

When Frieda Belinfante, part of a Dutch resistance group, decided to sell her cello as a means to sustain her life in the underground and took the risk to approach an unknown, but rich company owner as a potential buyer, he asked: How come you trust me? Frieda said: Well, I go by faces. That’s all I have to go by. I don’t know.

Heinz Dörmer, imprisoned from 1941 to 1944 at Neuengamme concentration camp remembered: They were terrible times. You were never safe. When the doorbell rang or there was a knock on the door, you always thought the worst.

It was silence for Pierre. Pierre Seel, 17 years old, deported for six month to the camp of Schirmeck, was released at the end of 1941. He was accepted back into his family under one condition: never to talk about the reasons of his imprisonment – his homosexuality. Upon my return from the Schirmeck camp, my father had imposed a pact of silence about my homosexuality, and that law persisted in our home: no revelations from me, no questions from them. /…/ Nightmares haunted me day and night; I practiced silence.

Under Nazi rule, homosexuals, men and women alike, came under pressure. State persecution – through tightened laws and special police units – focused on male homosexuality and led to the arrest of app. 100,000 homosexual men. Lesbian women, while spared such a massive persecution, had to mask their lives once again. Personal testimonies show how individuals came under pressure in a treacherous environment. A look back at history that also raises questions about the present: how strong is the recently secured position of homosexuals in society? How would family, friends or colleagues react today?

Within the racial ideology of the Nazis, population growth and racial purity were proclaimed as essential values of the future ‘Aryan race’. The 1935 Nuremberg laws stripped German Jews of their citizenship and prohibited sexual relations with persons of “German blood.” Abortion was penalized. At the same time a stricter version of paragraph 175 criminalizing male homosexuality was introduced. Male homosexuals were publicly marked as enemies of the state.

An estimated 100,000 men were arrested on suspicion of homosexuality during the Third Reich. Half of them were convicted and sent to prison. After completing their prison sentence, 10,000 and 15,000 of these men were deported to concentration camps, mostly in Germany and Austria. Unlike Jews, they were not sent to death camps or killed in gas chambers. In theory, homosexuals were ‘re-educated’ through hard labour. In practice, their chances of survival were low. An estimated 60 percent of homosexual camp inmates did not survive.

In whom can I still trust? investigates the lives of gay men and women during the Nazi era through individual stories. These stories illuminate how civil society acted as accomplice and, sometimes, why people acted as they did. There are no easy answers. We look at the mechanisms at work in a totalitarian society that controls its subjects into the most private and intimate moments of their lives.

The exhibition reflects research based on a multitude of Gestapo, police, camp, hospital and court records that historians only recently have looked into. I am also especially indebted to gay survivors who allowed me to share their story, mediated through many conversations I had with them since the early 1990’s. Some of these interviews you will be able to see in my documentary film Paragraph 175 which will be shown tomorrow at the Labia Theater.

For the longest time, we did not know the men with the pink triangle [the marking for homosexual inmates in the camps]. The Nazi invention of the pink triangle was able to become an international symbol of gay and lesbian pride because we were not haunted by concrete memories of those who were forced to wear the pink triangle in the camps. No names, no faces, an empty memory.

Nazi paragraph 175 remained on the books in West Germany until 1969, with again nearly 100,000 men being arrested. Gay survivors were forced to stay underground. Only three written testimonies of gay survivors were ever published. They were traumatized by the refusal to recognize their torment. Some came to believe that their victimization was their individual fate and fault. The shame, the ongoing persecution, the isolation constitute a disturbing silence: The speechless victim.

With exceptions, publications documenting their individual fate only appeared in the 1990’s. I want to emphasize the important work of Lutz van Dijk in this process.

HOW TO TELL THIS STORY IN AN EXHIBITION?

Instead of a timeline, a chronology I wanted to look at the human fabric that allowed this to happen, the ethic choices people made, and the unanswered questions. The exhibit IS developed along four themes: trust, love, identity, death.

Theme (I) TRUST – In whom can I still trust?

Rumors, denunciations, anonymous letters. How did the police get their information on suspected homosexuals? Many eyes could turn the visit of a friend, the night at a hotel, or the eye-contact in the subway into ‘evidence’ of a gay encounter: In Berlin, 62% of all denunciations came from private persons or originated in the work sphere. Many of those sentenced to prison in the early years of the Nazi regime were released and could start their life anew. But could they really? The exhibition explores that question.

WHAT HAPPENED TO LESBIAN WOMEN?

The visible lesbian culture of the 1920’s was destroyed after 1933. Once again lesbian women stood without a supportive collective. Couples living together felt pressure from neighbors; some chose a protective fake marriage. Although the Nazi version of paragraph 175 ultimately was not extended to include lesbian women, lives were deeply affected by the emphasis of the Nazi regime on motherhood, traditional gender roles and the denunciation of lesbianism as ‘un-German’.

Theme (II) LOVE – Do you still love me?

The exhibit looks at the mechanism of betrayal – as well as support. Bystanders and helpers often were part of a family, a circle of friends, of professional networks. How did your environment react to a possible arrest? The second theme reminds us that people will, and can, always make choices. Some gay men were missed: mothers wrote letters to their sons in camps; friends warned them of possible arrest; colleagues were silent when questioned by the police.

Theme (III) IDENTITY – I am a human being, an individual. I am not a category.

The third theme reflects each human being’s fundamental hope of being seen and respected as an individual. In biographical sketches individual homosexual men and women are presented, including one story of two gay emigrants who escaped to South Africa. —- Can we reconstruct all lives of those who perished?

Theme (IV) DEATH – Did I ever live?

In contrast, the last panel shows the impossibility to recount the lives of all victims. Persecution often resulted in their disappearance altogether. Sometimes, only traces are left: a mug shot from a camp; an entry in a prisoner list.

It is a space of silence, of remembrance of those who were not remembered.

WHAT HAPPENED AFTER 1945?

In the post-war decades, former gay inmates were excluded from recognition and restitution. The victims of the Nazi paragraph 175 were not regarded as victims of the Nazi regime, but as ordinary criminals. 1945 meant the defeat of Nazi Germany as a state, but its totalitarian ideologies continued to be contaminating.

THE 21st CENTURY – WHERE ARE WE NOW?

Nearly 70 years after World War II, the position of homosexual men and women in Europe has improved strongly, legally and culturally. That also came from a (belated) reaction to the Nazi persecution of homosexuals who were finally recognized as victims at the end of the 20th century.

In close to 80 countries, laws today prohibit sexual activity between adults of the same sex. Uganda is seeking to introduce the death penalty and even considers prosecuting anyone who does not denounce homosexuals to the police. Russia is in the process of reintroducing repressive legislation for LGBT people. Transgender people in many countries experience discrimination and violence.

There is hope. In 1994, South Africa became the first country to protect sexual orientation from discrimination in its Constitution – and thus translated its understanding of the past into the rule of law. Over the last years, LGBT and human rights have been rising on the international agenda. South Africa, again, spearheaded the first UN Resolution on Human Rights, sexual orientation and gender identity. Argentina adopted landmark legislation in recognition of gender identity. The US and the European Union identified LGBT rights as a cross-cutting priority in foreign policy. The groundbreaking 2006 Yogyakarta Principles applied International Human Rights Laws to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity.

I do believe that we are on the brink of developing global legal parameters for LGBT human rights. However, globalization is the big distributor, in good and bad: as the struggle for LGBT rights goes global, homo- and transphobia increasingly are sponsored globally, through fundamentalist religious leaders, neo-colonial or nationalist agenda’s. These echoes of hate will shape the lives of many.

Each society is characterized by whom it excludes from its midst: the recognition of LGBT lives will define the ethic core and humanity of societies in the 21st century. Since 2004, more than 20 lesbians, transgender and gays have been brutally killed in South Africa. More might have been raped and tortured without being documented.

How will South African civil society react to this hate and murder? Can lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender count not only on protection under the law, but by the society they are part of? Will other countries give in to intolerance, or help to advance the equality and protect the dignity of all their citizens?

In an increasingly interconnected world, museums have an opportunity to raise the global scale of their topics and to trace the many questions that the past has left unanswered for the present to address. Museums are about people and our future, especially when they deal with the past.

The South African Holocaust & Genocide Foundation embraces its mission of civic responsibility and building community through addressing these questions at a time that hate towards lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender still is poisoning civil societies, religious communities, and governments.

I do thank Richard Freedman for his courageous leadership, and his staff for an enormous effort in the redesign of this exhibit. Its designer Linda Bester did excel all my hopes, and I rarely experienced such a professional, warm and elegant cooperation across the many, many miles that did not divide, but connect us.

To see this exhibition here, in South Africa, starting a new life, is a very large gift for me, and I thank you dearly.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCE SPEECH

Klaus Mueller: Opening speech of exhibition IN WHOM CAN I STILL TRUST? Homosexuals during the Nazi era. South African Holocaust & Genocide Foundation, Cape Town 2013, Feb 13, 2013.

Museums and challenges of the 21ST CENTURY (London 2008)

(PLEASE SEE ALSO HERE.)

The below arguments all circle around one assumption: museums will not continue to exist in their present 150-year old form for the foreseeable future, at least not as relevant institutions. As many other businesses, they face a rapidly changing culture, through which their mission will be redefined and will take on new meanings.

They are challenged in their core definition as showcases of material culture through the most innovative force in contemporary culture, the Web. The unprecedented access to billions of replicas of cultural artifacts will lead to significant changes in how we look at, consume, or produce cultural artifacts. Virtuality, both in its narrower technological and its broader cultural meaning, will prove itself as a fundamental category of museum practice.

Narration – as a form of reflection, interpretation and representation of culture – will become the fluid core of what museums are about. Traditional one-way presentations of expert institutions (such as museums) will be altered by the ongoing transformation from collection-based to audience-driven missions and, equally, by two-way Web 2.0 communication models, both on- and offline.

Museums will need to translate the potential of user generated content for their field, as other industries have done before. As an expert institution they will be part of an ongoing reevaluation of what expertise still means in contemporary culture. And while they are localized institutions being physically defined by the space in which they function, their visitors – both local and global – today come from unprecedented diverse national, religious and cultural backgrounds.

The physical space of museums will remain important as temples of civic and secular sacred spaces in contemporary urban life. But their physical structure is the shell that museums partially need to leave behind. Their relevance will be defined through a much broader local/global network and their success in claiming venues outside their onsite structure.

(I) THE CONVERSION OF THE REAL AND THE VIRTUAL LEADS TO A REEVALUATION OF THE MUSEUM’S CORE DEFINITION AS A SHOWCASE OF MATERIAL CULTURE

The World Wide Web is redefining core museum tasks as collecting, preserving, and exhibiting. The current digitization of millions of objects in digital heritage programs leads to new forms of collections management and unparalleled access to replicas of museum artifacts. This transformation is changing museums as we know them: it inspires new forms of preserving, displaying and understanding cultures both on- and off-line.

An exploration of museums and virtuality benefits less from a statement of their differences than from an investigation of common grounds and shared objectives. Put simply, on-site museums and their online counterparts are merely two ways of exhibiting cultures.

Despite the considerable and costly digitization efforts few museums have so far fully embraced the diverse potentials of an unlimited space for display and communication. While other industries expanded and reconfigured their business through the Web in the last years (or were forced to do so), museums approached its potential with a mixture of caution and distance. Old debates (e.g.: are museums about objects or are they about ideas?) color the ambivalence regarding the relevance of virtuality for the ‘museum experience’.

As museums traditionally define themselves as showcases of material objects that visitors can experience on-location, the virtual display mode of the Web appears to be a distortion of this encounter. But does this assumed dichotomy of the ‘authentic’ versus the ‘copy’, of the ‘real’ versus the ‘virtual’ really help us to understand what museums are about?

Artifacts may tell a story, but they do so within the curatorial and architectural meaning and structure given by the larger museum display. This is why “Virtuality” has been and will remain a fundamental category of exhibiting practices. The integration, preservation and interpretation of the museum artifact through collection and exhibition in an Onsite Museum remove and alienate the object from its ‘authentic’ environment. They introduce a new and virtual “museum order” and add a frame of meanings to the artifact. It is the object’s physical presence within this new curatorial context that traditionally constituted the ‘museum experience’.

Methodologically, the virtual representation of objects on Museum Websites only mirrors and re-configures that earlier transfer of the object from its ‘authentic’ (original, historical, physical or emotional) context into the museum environment. As museums redefine the value and meanings of an artifact by taking it into their collection, its digital counterpart on the Web challenges the frame of reference one more time. Thus, re-location of objects is not new to museums, but its very rationale. Museums are experts in framing objects in ever new contexts, and the Web is just one of them.

Notions of virtuality usually have a technological basis. Digitization hereby refers to the transfer of existing information and the reproduction of physical objects in an electronic form. But do virtual reproductions simply mimic their real counterparts? I find that definition too restrictive; digitization is more than a reproduction technique. Etymologically speaking, virtuality comes from the Latin virtus, which has several meanings, including excellence, strength, power, and (in its plural form) mighty works. The word describes a modus of participation or potentiality. In this sense, virtual objects can be seen as illuminating the potential meanings of art and other objects. Virtual exhibitions contextualize objects through narratives, just as onsite exhibitions. Virtuality should be understood as a complex cultural interpretation of objects that forces us to rethink the tangible and intangible imprints of our cultural history.

Debates on ‘virtuality’ refer back to fundamental debates on art and reproduction technologies, as instigated by Walter Benjamin’s 1934/35 essay on The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Benjamin’s dictum that art looses its aura and immediacy of experience through the possibility of its mechanical reproduction (its reproducibility) was much quoted in today’s debate of ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Digital Reproduction’, led by Jean Baudrillard, Paul Virilio and Stuart Hall. His analysis marked the incision mass reproduction of art meant for our perception: The digitization of artifacts and their worldwide accessibility through the Web radicalizes this incision one more time.

The translation of museum objects into electronic representations renders both gains and losses. The much-praised social and civic space in which the object is experienced is lost. The digital reproduction appears foremost as visual (or aural) information, similar to a document. Although in galleries visitors experience the objects in a spatial order, they usually cannot touch the objects. Virtual programs eliminate the physical dimension altogether as well as the momentum created by the object’s physical presence; after all, bytes have no aura. But the digital copy can offer new venues for contextualizing the object and investigating its informational layers as well as interactive options for exploring its material characteristics and history.

The manifold bonds between the physical and the digital in today’s world have blurred the distinction between real and virtual: They increasingly overlap, feed on each other, become inseparable.

Museums can no longer assume that they will continue to exist in their present 150-year old form in a culture that radically is changing our notions of reality/virtuality or is multiplying our access modes to culture. The museum’s core definition as a beholder of ‘authentic artifacts’ has lost its once obvious meaning in a world that no longer functions in a simple dichotomy of ‘authentic’ versus ‘copy’. The boundaries between the real and virtual have become fluid, ambivalent and multi-layered. The narration of material/virtual culture – as a form of reflection, interpretation and representation – will become the fluid core of what museums are about.

(II) USER-GENERATED CONTENT WILL CHANGE THE FUNCTION OF MUSEUMS

The Web, and with it our culture, is changing rapidly. It is impossible to predict how it will look in five years time. Let me try anyway: My first prediction concerns sharing as the new mode of how we deal with information. The availability of information including access to cultural artifacts will be seen as a given and change our ways of looking at, consuming or producing culture. If museums do not share their expertise through the Web in multiple ways, they will become dead institutions with a limited lifespan.

Look at the example of Wikipedia, the encyclopedia that relies on volunteers who by now assembled 8.2 million articles in more than 200 languages, or about 15 times as many as the largest edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. It has become the 8th most visited Web site on the Internet. When did Wikipedia start? In 2001. If a volunteer initiative like Wikipedia can challenge an institution like the Encyclopedia Britannica within just a couple of years, you know something is happening. In research Wikipedia was found about as accurate in covering scientific topics as Britannica, which happens to pay its research staff.

Look at Flickr.com, a 2.0 web innovator, which offers a platform for the presentation and exchange of photos. In 2006 it had 4 million users and app. 180 million photos. Today it hosts 2 billion photos. When did is start? In 2004. Newspapers, TV and other media pay attention to FlickR, as they increasingly have the fastest photo shoots from around the world. In 2008 the Library of Congress became the first partner in a pilot project called Flickr commons: The Library team has chosen about 3,000 photos to show on Flickr Commons and invite visitors to help them tagging the photos. Besides using a new venue for showing their collection, the Library of Congress hopes to enhance the quality of their bibliographic records. 24 hours after the photos were put online, the Library had received 4,000 tags and 500 reactions.

A new environment brings new questions. A museum defines itself through its collection. But once information about that collection is transferred into a database, does it matter where the database originates or is accessed? How important is a museum identity in a digital world, and how can it be sustained? Furthermore, while the ownership of intellectual property on the Internet is debated, it seems clear that many Web users do not concern themselves with the provenance of their downloads. What does this mean for museums?

My second prediction: The Web will become a competitor to and co-operator with museums. Initiatives on the Web that take on museum functions will become more visible. They might be faster, smarter and better in an online environment and might easily find larger audiences. The history of other service industries shows us how rapid the Web can redefine the core of their business.

Look at Myspace.com or YouTube.com where users can present their own videos, music, photos, or poetry. When did YouTube start? In 2005. A year later, it had six million users who put an average of 60,000 new videos on the site each day. MySpace started in 2003 and only three years later had 93 million users. MTV and other music channels, which dominated our consumption of music for a long time, might be history: More and more artists use MySpace to present themselves. The Web is the new creative experimental lab.

In recent years, 1.5 billion Web sites, including millions of individual sites, have been established. Never before have such large numbers of people become producers of cultural content, seeking only the respect of their peers as their main reward. In a way, the Web has become a wildly disorganized museum of humanity, a cabinet of wonders and curiosities (and its search machines serve as rather confused curators…).

My third prediction: Museums become producers on the Web everywhere. Museums will be understood as centres of expertise that offer their information not just in the building, on their website and in their publications, but in a variety of online media and networks with similar topics. Create once, produce everywhere. As digital information in whatever form is not bound to a particular location, museums will become producers accepting their audiences as co-producers and actively seeking a proliferation of spaces to reach visitors wherever they are.

And last, not least, the fourth prediction concerns a reversal of roles: Users will generate museum content. Museums saw their audiences as entities they are going to offer information, teach and educate. In the future they still will do that, but in a dialogue: our visitors will offer us information, teach and educate us about our mission and collections. User-generated content – common in many other industries – has just started to change core museum policies regarding collecting, documentation and exhibition. Maybe in some years we will look back with a sense of bewilderment that an institution, which thrives on the appraisal of culture as an expression of the human condition, has been operating for so long without enabling its visitors to contribute to its work.

(III) THE RETURN OF THE EXPERT

While contemporary culture seems to turn all of us into cultural producers, or at least give us the respective tools, the role of the expert and expert institutions like museums have become unclear. The wisdom of the masses, as instrumentalized by Wikipedia, seems to diminish traditional hierarchies of power, knowledge and expertise. And yes, money. While Google, Youtube or Myspace have developed into powerful companies, none of us free floating producers of websites and cultural information has been paid for what we contributed to that success. We have become free and cheap assets.

While museums need to translate the potentials of user generated content for their business, they also face the question of how they can prevail as an expert institution and how expertise will be valued (and paid for) in the future. Being conservative institutions trusted by the audience more than any other public institution, museums might be able to cast themselves as a leading voice in the necessary reevaluation of expertise in contemporary culture. The future of museums will be partially shaped by this new balance between traditional expertise and the wisdom of the masses.

(IV) THE EFFECTS OF GLOBALISATION ON RELEVANCE: WHERE IS HOME?

The Web is not the only challenge to the context, in which museums operate. Globalisation effects also force museums to re-evaluate their mission. Their onsite and online audiences are changing dramatically.

While some praise the liberating effects of free trade and greater global communication, claiming that marginalized groups are empowered as a result, others fear standardization and forced assimilation into a Western-dominated world. Like it or not, the development to an increasingly interdependent world is a given: What role will culture, and more immediate, museums, play in this new globalization movement?

What should museums in the 21st century attempt to achieve? Relevance.

When is a museum relevant to its visitors? If visitors feel that a museum offers something to their life and that is develops, in dialogue with them, within the very same society of which we are all part off. Ideally, but that already is the high art of museum making, a museum becomes a natural point of reference or even authority in its area. A hub of connectivity, a docking station for people, ideas, discourse.

While this often was more of a utopia than a reality, these goals are increasingly more difficult to reach due to the differentiation of our audiences.

Museum visitors are traveling more than ever before. Tourism has become the world’s largest growth industry, and museums have become key partners. Heritage travel is one of the fastest-growing segments of domestic and international tourism. Four out of five of the top tourist attractions in the U.K. are museums. Cultural enrichment has become an incentive of mass tourism. As a consequence, the number of museums and heritage sites is rising worldwide, as is the percentage of the regional and foreign visitors they attract.

Migration has equally changed the context in which museums operate. According to a United Nations International Migration Report in 2002, 56 million emigrants live in Europe, 50 million in Asia, and 41 million in Northern America. As museums strive to determine their civic role and build partnerships with their constituents—often a “local” focus—they also are challenged to communicate with and serve national and international audiences—the “global” focus. Urban centers have become transnational areas that are no longer defined solely by their nations, but by the ever-changing mix of permanent and temporary residents with widely diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds. Globalization is happening right in our own neighborhoods. Interaction with these diverse constituencies, both transnational and local, is challenging museums to develop new communication skills.

Off course, globalization is not only changing our audiences, but also us as museum professionals. No longer do our models come solely from around the corner. Networks across national borders have become a given.

Museums have been remarkable successful in understanding and creating public and civic space. They have become the new cathedrals, at times sacred spaces, in which visitors want to experience themselves and others. Cities worldwide build museums in order to pacify and civilize public space. Museums have become tools of successful city branding, and some museums like the Guggenheim, the Louvre, or the Hermitage have used their brand name to create satellite museums across the world. But for most museums, globalization means a rediscovery of their local environment: their visitors, their staff, their collections, their tools to reach out to larger audiences, their mission in a quickly changing world.

A more inclusive mission will determine both the ethical signature and economic endurance of museums in a global world. The corporate world is more advanced in communicating across lines of ethnicity, language, nationality, gender, sexual orientation or religion. Museums can profit from this expertise as well as avoid the pitfalls of the often-superficial localization strategies that corporations use for their global products. Museums do not offer commercial merchandise, but cultural experiences. It is in this market of experiences that globalization challenges museums. Many businesses today sell their products in part by using museum display techniques in their overall strategies. Museums have to compete with many components in our economy of experiences without losing their distinctiveness and, especially, credibility.

The proliferation of national museums in the nineteenth century was a consequence of the development of nation-states. So how will national collections be affected by the transnational networks of the twenty-first century? Could museums move to the forefront—as they did in defining a national consciousness in the nineteenth century—by guiding their audiences into a pluralistic and transnational understanding of culture?

After all, museums know, maybe better than any other institution, that cultural artifacts are hybrid in nature: products of cross-cultural influences. Isn’t cultural diffusion as old as mankind? Off course, globalization in the twenty-first century has radically accelerated the scope, speed, and depth of cultural distribution. Some assume that this will turn a few into producers, many into consumers, and all of us into members of a McWorld. Others embrace cross-cultural exchange as the breeding ground of new cultures. Will museums learn from best practices around the world while keeping their distinctiveness? Or will they merge into a globally indistinguishable model? The global museum—a copy-cat?

As globalization takes us perhaps inevitably toward a standardized consumer culture, museums face some challenging questions. Can they make a meaningful contribution to the preservation of cultural diversity? Can they effectively document the isolation of marginalized groups, the disappearance of culturally specific traditions, or the alienation felt by immigrant residents? Just as museums have established biodiversity policies that help to sustain the natural ecosystem, can they—or should they—also strive to safeguard the “cultural ecosystem”?

With their collections as their core, and with their missions of civic responsibility and building community, museums, more than any other institution, might have the potential to create real understanding between cultures. Museums at their best have the special ability to make us feel—wherever we come from—culturally “at home”.

But home is not an easy experience in a world where everything seems to be connected with everything. Museum generate global attention through ever more impressive cultural cathedrals. Their peaceful civic spaces seem to bridge and negotiate cultures.

But global attention comes at a price. ‘Ownership’ will become a major issue for all museums due to the increase in international travel and the accessibility of vast new amounts of historical records and related data. As our frames of reference continue to expand, international standards—for example, codes of ethics and guidelines concerning the handling of unlawfully appropriated objects—are becoming more widely accepted around the world.

The growing global conflict between the freedom of artistic expression versus religious sensibilities no longer can trust on the merits of argumentation alone: like artists before them, museums might find themselves suddenly targeted if they do not avoid conflict and take a stand. A museum can’t be an institution of everything for everyone. It operates on a mission for which reason it is brought to life, and following its mission, it must claim a position of truthfulness to its goals and of leadership in this field.

Courage is not an easy gesture for a public institution. Will museums choose to be civic leaders and contribute to strengthening a democratic dialogue?

BIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCE: Klaus Mueller: Museums and the challenges of the 21st century. In: Future of Museums. New Thinking about Museums of the Future. London, City University 2008.

CITY MUSEUMS as a HUB OF CONNECTIVITY

In: A city museum for the 21st century, Stuttgart 2007

As a preparation for this conference on the future city museum of Stuttgart I thought it would be a good idea to use my travels, if time allowed, visiting city museums. Off course, eclectic travel does not constitute an empirical base to speak off. But it provides anecdotic impressions or, in my case, at least it testified to the fact that the god of the city museums was not with me.

In Washington, I found, I came too late; the city museum had ceased to exist: lack of interest, lack of funds. Rome, on the contrary, certainly made me feel very special as a visitor: But then again, I was the only one. And it remains an eerie experience when visitor service walks ahead off you to turn on the light. In Vienna – (there was light; there were other visitors) – I remember two things: stumbling onto a neat replica model of Vienna anno 1420, complete with the Jewish quarter and synagogue (which, however, nobody mentioned on the story next to the replica, was completely annihilated with its inhabitants one year later) and my difficulty to find Vienna’s 20th century. Well, it took me a while to realize that there is no 20th century in the Vienna city museum.

I was a bit depressed after these visits. These institutions did not seem relevant. Neither to its topic, nor to its visitors. Which gives the easy answer to the first question: what do you ask a city museum in the 21st century to achieve? Relevance.

But when is a city museum relevant to its visitors? If visitors feel that a museum offers something to their life and that is develops, in dialogue with them, within the very same society of which we are all part off. Ideally, but that already is the high art of museum making, a museum becomes a natural point of reference or even authority in its area. A hub of connectivity, a docking station for people, ideas, discourse.

A city museum, like all museums, is a service institution that needs to find out how to best serve its public. Off course, a museum can’t be an institution of everything. It operates on a mission for which reason it is brought to life, and following its mission, it must claim a position of leadership in this field. Clearly we are not waiting for an institution that just wants to be there. While a museum, ideally, brings together expertise, knowledge, and objects to develop its mission, it needs to build bridges into the communities it wants to talk with.

As museums strive to determine their civic role and build partnerships with their constituents—often a “local” focus—they also are challenged to communicate with and serve national and international audiences—the “global” focus. Urban centers have become transnational areas that are no longer defined solely by their nations, but by the ever changing mix of permanent and temporary residents with widely diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds. Globalization is happening right in our own neighborhoods. Interaction with these diverse constituencies, both transnational and local, is challenging museums to develop new communication skills.

A museum exists by the grace of communication. In this sense, visitors are co-owners. It is their museum. Only then visitors will be willing to consider this place of learning as their place to turn to, to engage with, to fund, to take into account. Which issues should a city museum address and which questions should it put forward to its visitors?

A city museum is a reflection of an increasingly globalized urban hub. The more we come from all places, the more we struggle with the longing for home, our sense of identity, the possibility of human connections, and the art of peaceful dialogue. The old circle of questions: where do we come from, how did we become what we are, and where are we going from here has not become easier to respond to. But it might serve as a frame for our questions towards a city museum and for its audiences:

– How can we strengthen a sense of home and connection despite and with our diverse backgrounds and conflicting values?

– How do we support respect for identities in all their shapes while building an understanding that people change and have the right to do so, especially when they question the traditions they were brought up in?

– What are the connective tissues in our differences: family, friends, the pursuit of happiness, religion, work, sex, the place we inhabit?

– How can we strengthen a democratic dialogue?

With their collections as their core, and with their missions of civic responsibility and building community, museums, more than any other institution, have the potential to create real understanding between cultures. Museums at their best have the special ability to make us feel—wherever we come from—culturally “at home”.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCE LECTURE

Klaus Mueller: Remarks. In: A City museum for the 21st century. Documentation of an international expert hearing for the planned city museum of Stuttgart, Sep 25-26, 2007.

Opening speech Exhibit at DUTCH PARLIAMENT 2007

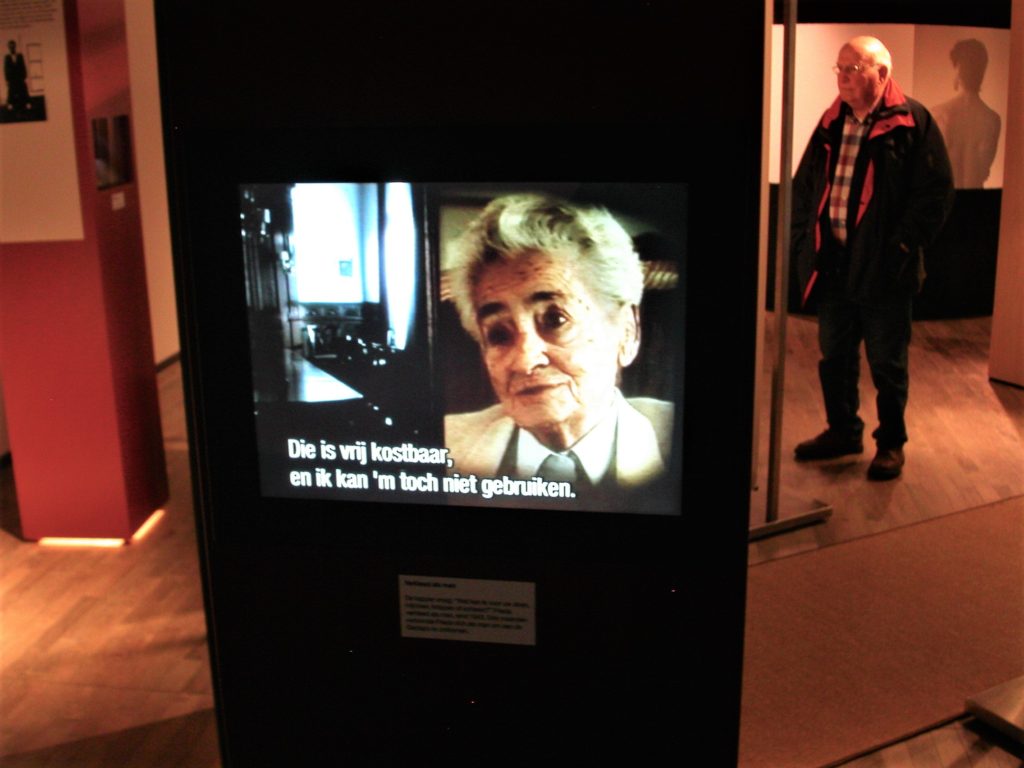

foto: Frieda Belinfante in interview

TOESPRAAK KLAUS MUELLER TWEEDE KAMER DEN HAAG 22 MEI 2007

Veel mensen zouden er blij en trots zijn dat deze tentoonstelling vandaag in de Tweede Kamer opent. Maar ze zijn er niet meer. Ze kunnen dit moment van empathie voor hun lot of de herkenning voor hun verzet niet meer zelf meemaken. Ze bleven alleen met hun herinnering.

Aan een van hen wil ik graag vandaag de tentoonstelling opdragen: Frieda Belinfante, geboren in Amsterdam. Ik ontmoette haar in mei 1994 in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Toen was ze 90 jaar oud.

Tijdens onze voorafgaande gesprekken had Frieda duidelijk gemaakt dat er niet veel tijd meer was. Zij had terminale kanker. ‘I will try to stay alive until you come to interview me. But I can’t promise it. So you better hurry up.’

Het werd een zeer bijzondere ontmoeting voor mij. Frieda had besloten over haar leven te praten, dat getekend was door haar ervaringen tijdens de Duitse bezetting – en ik was notabene Duits. Maar wij deelden ook iets, onze homoseksualiteit. Frieda besloot voor de eerste keer openhartig ook over dit aspect te praten.

Haar leven werd vergaand getekend door haar beslissing om in het verzet te gaan. Aan haar veelbelovende muziekcarrière als eerste vrouwelijke dirigent in Nederland kwam abrupt een einde. Frieda nam deel aan het kunstenaarsverzet, de vervalsing van persoonsbewijzen en – samen met de eveneens homoseksuele verzetsleider Willem Arondéus – de aanslag op het Amsterdamse bevolkingsregister in 1943. Haar lesbisch-zijn was niet de reden waarom zij in het verzet zat, maar kleurde wel haar positie. Als onafhankelijke vrouw was zij gewend haar eigen beslissingen te nemen. Op de vlucht voor de Gestapo liep ze een tijd als man door de stad voordat ze naar Zwitserland kon vluchten.

Na de oorlog voelde ze zich niet langer thuis in Nederland. Veel van haar Joodse collega’s overleefden niet. In haar zicht ging iedereen door alsof er niets gebeurd was. Ze emigreerde naar Amerika. Ze keek niet terug. Ze paste niet meer in dit land.

En zij paste niet in de geschiedschrijving van het verzet. Over haar niet beschreven rol in het Amsterdamse verzet was ze duidelijk: “Ik heb gewoon mijn leven geleefd, was nooit een rolmodel of deel van een collectief. Maar het kan natuurlijk niet zo zijn dat Willem Arondéus en ik verdwijnen uit het collectieve geheugen, alleen maar omdat wij homoseksueel zijn.”

Een collectief geheugen wordt mede gevormd door wat tegenwoordig de politics of memory heet. Nationale beeldvorming is een gestuurd proces. Lange tijd werd het verzet gebruikt als symbool van nationale trots. Verzetshelden werden als respectabele mannen neergezet: voor homo’s, en vaak ook voor vrouwen, was geen plek in deze eregalerij.

Niet in het verzetsverhaal. En ook niet in het vervolgingsverhaal.

De tentoonstelling ‘Wie kan ik nog vertrouwen?’ laat zien hoe het individu in een totalitaire staat onder druk komt te staan en hoe een medeplichtige maatschappij verregaand daaraan bijdraagt. De reductie van het individu tot een categorie is het uitgangspunt van een totalitaire staat en van totalitaire denkbeelden – toen en nu.

Met de ondergang van het nationaal-socialisme zijn diens totalitaire opvattingen niet verdwenen. In een grote hoeveelheid staten worden homoseksuelen vandaag vervolgd, gevoed door fascistische, communistische of religieusfundamentalistische regimes. De locaties zijn veranderd – totalitair en racistisch gedachtegoed is gebleven. Ook democratische staten hebben problemen met groeiende fundamentalistische stromingen van christelijke, joodse, of islamitische signatuur en met neofascistische ideologieën.

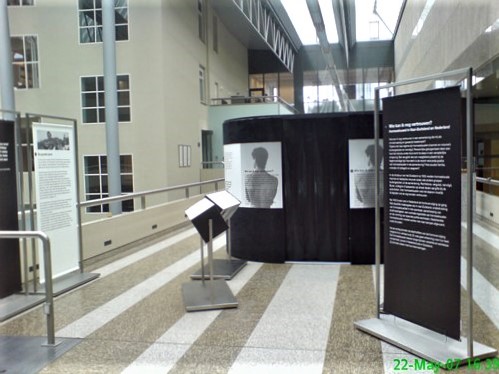

foto: tentoonstelling in Dutch parliament, The Hague

Zestig jaar na de Tweede Wereldoorlog is de positie van homoseksuelen in Europa verbazingwekkend verbeterd. Vooral in Nederland dat lange tijd de voorvechter op het gebied van de homo-emancipatie was. Maar vrijheid en tolerantie blijven a work in progress. Ook hier moeten homorechten opnieuw worden verdedigd.

Homoseksuelen kunnen hier zoals iedereen hun leven leiden. De gouden jaren van onbezorgdheid lijken echter voorbij. Wie kunnen wij nu vertrouwen? Kunnen homoseksuele mannen en lesbische vrouwen in Nederland, in Europa blijven rekenen op rechtsbescherming? Of worden veroverde vrijheden ingeleverd – op straat door dreiging met geweld, op school door het wegpesten van homoseksuele leraren of scholieren, bij het asielrecht door het terugsturen van homoseksuele vluchtelingen naar landen waar de doodstraf op homoseksualiteit staat?

Hoe zal zich de samenleving opstellen tegenover groeiende intolerantie en onbegrip in een open samenleving? De Europese Unie is gebouwd op normen en waarden: hoe gaan wij ermee om dat de Poolse regering deze niet langer wenst te achten als het om homoseksuelen gaat?

De tentoonstelling over de jaren 33-45 laat zien dat homoseksuelen – zoals iedereen – familie, vrienden, collega’s, buren hadden: hoe reageerden die toen op hun bedreiging? De verhalen tonen dat mensen ook in een dictatuur keuzes hebben en maken. De tentoonstelling legt vragen voor aan de bezoeker: wie kan ik nog vertrouwen in een dictatuur? Waarom steunt mij de één, en verraadt mij de ander?

En wie herinnert zich? Bij het maken van de tentoonstelling viel mij op hoe schaars het materiaal is. Over de homogeschiedenis in de 20ste eeuw, zowel de zwarte bladzijden als de successen vanaf de jaren zestig, is weinig terug te vinden in Nederlandse musea of archieven.

Ze hebben hun collectie zelden vanuit dit perspectief bekeken. Er wordt niet doelgericht verzameld. Men kan dan ook vaak geen expertise bieden. Er ontbreekt een structureel beleid bij erfgoedinstellingen om de homogeschiedenis te integreren in het nationaal geheugen.

Homoseksualiteit wordt nog steeds gereduceerd tot een geschiedenis van seksualiteit. Het leven van lesbische vrouwen en homoseksuele mannen in de twintigste eeuw werd echter niet bepaald door hun seksueel gedrag, maar door de maatschappelijke, medische, juridische en symbolische uitsluiting door de samenleving.

Homogeschiedenis is dus Nederlandse geschiedenis tot in de haarvaten.

Een samenleving definieert zich ook door wat ze bewaart en koestert. Het collectieve geheugen werkt als een filter. Waar komen wij vandaan, hoe zijn we zo geworden, waar gaan wij naartoe?

Ik hoop dat deze tentoonstelling een aanzet voor musea en archieven is de homogeschiedenis in de 20de eeuw in al haar verscheidenheid in kaart te brengen, te bewaren en deel te laten worden van ons nationaal geheugen.

LBR-LEZING 2006 ‘WIE KAN IK NOG VERTROUWEN?

Verzetsmuseum Amsterdam, Jun 8, 2006

NOTE: Op 8 juni 2006 gaf dr. Klaus Mueller de jaarlijkse LBR-lezing (nu Anton de Kom-lezing) in het Amsterdamse Verzetsmuseum. ‘Wie kan ik nog vertrouwen? Homoseksueel in nazi-Duitsland en bezet Nederland’ schetst de vervolging en het verzet van homoseksuelen tijdens de nationaal-socialistische overheersing. Dr. Klaus Mueller is de samensteller en historisch onderzoeker van de tentoonstelling Wie kan ik nog vertrouwen? homoseksueel in nazi Duitsland en bezet Nederland, die sinds 21 april te zien is in Herinneringscentrum Kamp Westerbork.

Wie kan ik nog vertrouwen? – Ik wil beginnen met een verhaal. Een verhaal dat weliswaar meer dan zestig jaar geleden heeft plaatsgevonden, maar toch heel dichtbij, hier, op deze locatie. Het gebeurde in de nacht van 27 maart 1943 schuin tegenover het huidige Verzetsmuseum waar nu Studio Plantage is gevestigd. Een verzetsgroep pleegde er een aanslag op het toenmalige bevolkingsregister van Amsterdam om de bezetter het gebruik van persoonsgegevens onmogelijk te maken: voor hun jacht op joden, de identificatie van politieke tegenstanders en van Nederlanders die zich aan de oproep tot arbeidsdienst in Duitsland probeerden te ontrekken. Het was een van de eerste keren dat zich het Nederlandse verzet richtte tegen een collaborerende instelling. Het is ook het verhaal van Frieda Belinfante en Willem Arondéus die beiden aan de voorbereidingen deelnamen van deze aanslag.

Hun leven wordt verteld in het recent verschenen boek, dat ik samen met Judith Schuyf heb samengesteld, ‘Het begint met nee zeggen. Biografieën rond homoseksualiteit en verzet’. Het boek presenteert biografische portretten van homoseksuele mannen en lesbische vrouwen die aan het Nederlandse verzet hebben deelgenomen, maar daarna uit het collectief geheugen werden gewist.

Ik interviewde Frieda in 1995 in Santa Fe in New Mexico, ze was toen negentig jaar oud. Het was een zeer bijzondere ontmoeting voor mij. Frieda had besloten over haar leven te praten, dat getekend was door haar ervaringen tijdens de Duitse bezetting – en ik was ook nog Duits. Maar wij hadden een band zoals wij snel ontdekten: wij waren beiden homoseksueel. En Frieda besloot voor de eerste keer zeer openhartig ook over dit aspect van haar leven te praten.

Vandaag wil ik graag op deze bijzondere locatie mijn lezing aan haar opdragen. Aan haar dank ik de meest passende leus die ik kan bedenken voor deze jaarlijkse lezing in het teken van racisme bestrijding:

“EEN MENS IS EEN MENS, ZO IS DIE GEBOREN EN ZO MOET DIE LEVEN.“

Frieda’s leven werd vergaand getekend door haar beslissing in het verzet te gaan. Aan haar veelbelovende muziekcarrière als eerste vrouwelijke dirigent kwam in Nederland voor de bezetting abrupt een einde. In het verzet nam zij veel beslissingen op eigen houtje. Haar lesbisch-zijn was niet de reden waarom zij in het verzet zat, maar kleurde wel haar positie. Als onafhankelijke vrouw was zij gewend haar eigen beslissingen te nemen, maar ook vertrouwd met de noodzaak in het openbaar rollen in te nemen die haar lesbische identiteit beschermden.

Na de oorlog voelde ze zich niet langer thuis in Nederland. Tien procent van de Amsterdamse bevolking was door de Duitsers afgevoerd, mede geholpen door Nederlandse instellingen, en daarna vermoord. Veel van haar Joodse vrienden en collega’s overleefden niet. Vanuit Frieda’s zicht ging het land echter door alsof er niets gebeurd was. Ze emigreerde naar Amerika. Ze keek niet terug. Ze paste niet meer in dit land.

En zij paste niet in de geschiedschrijving van het verzet. Over haar niet bestaande rol in de geschiedenis van het verzet was ze duidelijk: “Ik heb gewoon mijn leven geleefd, was nooit een rolmodel of deel van een collectief. Maar het kan natuurlijk niet zo zijn dat Willem Arondéus en ik verdwijnen uit het collectieve geheugen, alleen maar omdat wij homoseksueel zijn.”

Frieda en Willem Arondéus hadden al voor de aanslag in Frieda’s woorden als ‘broer en zus’ in het verzet samengewerkt. Ook Willem Arondéus verdween voor een lange tijd uit het nationale geheugen. Hij had de aanslag op het bevolkingsregister geleid, samen met Gerrit van der Veen. Zijn advocate Lau Mazirel moest kort voor zijn executie aan hem beloven “na de oorlog aan de mensen te vertellen dat homo’s niet minder moedig hoefden te zijn dan andere mensen.” Zijn wens om als homoseksueel verzetstrijder te worden herinnerd stelde de naoorlogse hoeders van de nationale herinnering voor een moeilijke opgave. En die opgave mislukte. Lou de Jong beschreef weliswaar zijn leidende rol tijdens de aanslag en zijn homoseksualiteit, maar het was zijn verzetskameraad Gerrit van der Veen die postuum uitgroeide tot dé leider van de aanslag. (‘Gerrit van der Veen en zijn mannen’ heette dat.)

Pas in de jaren negentig werd Willem Arondéus herontdekt. Opeens was ‘heldendom en homodom’ – in de formulering van Jan Blokker – niet wederzijds uitsluitend. Was daarmee Arondéus’ laatste wens uitgekomen? Wat blijft is het beeld van een man die zonder aarzelen in verzet ging en die zich daar niet wilde verloochenen door zijn homoseksualiteit te verbergen. Zijn dood was voor hem een symbolisch offer van een homoseksueel voor de nationale eer. Zijn offer was verbonden met de hoop dat de zozeer verachte minderheid daardoor geaccepteerd zou worden na de oorlog. In dit laatste opzicht mocht zijn dood niet baten, maar deze inzet siert hem wel.

Een collectief geheugen komt niet alleen spontaan tot stand, maar wordt ook gevormd door wat tegenwoordig in de geschiedschrijving de politics of memory heet. Nationale beeldvorming is een gestuurd proces. Lange tijd werd het verzet gebruikt als symbool van nationale trots en samenhang. Verzetshelden werden als respectabele mannen neergezet: voor homo’s, en vaak ook voor vrouwen, was geen plek in deze eregalerij. Niet in het verzetsverhaal. En ook niet in het vervolgingsverhaal.

WAAROM WISTEN WIJ ZOLANG ZOWEINIG OVER DE NAZISTISCHE HOMOVERVOLGING?

De historiografie van het nationaalsocialisme en de Holocaust hebben lange tijd de nazievervolging van homoseksuelen zo goed als genegeerd. In de uitgebreide studies naar de bevolkingspolitiek en de rassenideologie van de nazi’s heeft homofobie, als een van de onderdelen daarvan, nauwelijks aandacht gekregen. Deze blinde vlek had zijn tegenhanger in de langdurige uitsluiting van de voormalige gevangenen met de roze driehoek uit de Holocaust herdenkingscultuur.

In de laatste vijftien jaar is door uitgebreid archiefonderzoek veel veranderd. Het door mij samengestelde en in oktober 2005 gepubliceerde Doodgeslagen, doodgezwegen. Vervolging van homoseksuelen door het naziregime 1933-1945 maakt de bevindingen van recent, vooral Duits onderzoek toegankelijk aan een breder Nederlands publiek.

Doodgeslagen, doodgezwegen is, net als het boek ‘Het begint met Nee zeggen’, onderdeel van een breder project dat het besef wil vergroten dat homovervolging integraal onderdeel is van het totalitaire karakter van het nationaalsocialisme en de Duitse bezetting. Homofobie wordt als structureel element van totalitair en racistisch gedachtegoed zichtbaar. Deel van dit project is ook de onlangs in Westerbork geopende en door mij samengestelde tentoonstelling Wie kan ik nog vertrouwen? Homoseksueel in Nazi-Duitsland en bezet Nederland die op 21 september wordt geopend hier in het Amsterdams Verzetsmuseum.

WAT WETEN WIJ VANDAAG OVER DE NAZISTISCHE HOMOVERVOLGING?

Een summier overzicht over de ontwikkeling in Duitsland, dan in Nederland.

In de bruisende jaren twintig kende de Duitse Weimar republiek voor het eerst een openlijke homoseksuele cultuur. Hieraan kwam een abrupt einde in 1933. In de nazitijd was een vermoeden van homoseksualiteit al voldoende reden voor arrestatie. Buren, collega’s of passanten op straat deden maar al te gretig aangifte.

Wij wonen twaalf jaar in een en hetzelfde huis, maar al die tijd is hij nooit met een meisje gegaan. Beweren kan ik natuurlijk niets, maar het komt toch erg verdacht op me over. Wat moeten al die jongens eigenlijk bij hem? Maar ik moet u verzoeken niet mijn naam te noemen.

Hedwig R. uit Wilmersdorf aan Gestapobureau, 1938

Er waren geen veilige plekken meer. Als homoseksuelen in staat van beschuldiging werden gesteld konden ze alles kwijtraken: hun eer, hun baan, hun woning, hun vrijheid.

Na de machtsovername in 1933 wilde zowel de Gestapo als de SS het oude en ‘inefficiënte’ sodomieartikel paragraaf 175 zodanig verbreden dat bewijsvoering niet langer nodig was. Dit wetsartikel bestond sinds de Duitse eenwording van 1871 en was gericht tegen anaal geslachtsverkeer. Omdat het echter moeilijk was aan bewijzen te komen, bleef het aantal vervolgde homoseksuelen laag tot 1933. In 1935 werden de Nürnberger wetten van kracht, die de joden van hun rechten beroofden en seksuele relaties tussen joden en niet-joden strafbaar stelden. In datzelfde jaar trad het herziene sodomieartikel in werking. Alleen al de verdenking van homoseksuele neigingen was nu genoeg om iemand te arresteren.

Eerder al werden homoseksuele en lesbische bars gesloten en organisaties opgeheven. Magnus Hirschfeld’s beroemde Instituut voor Seksuele Wetenschap werd al op 6 mei 1933 leeggeroofd door naziestudenten.

Ondanks deze gebeurtenissen kunnen sommige homoseksuelen aanvankelijk hebben gehoopt dat de praktijk minder erg zou zijn dan de leer, en wel vanwege de prominente positie van SA-chef Ernst Röhm. De SA was een paramilitaire organisatie, die met haar grove en intimiderende optreden de weg baande voor de opkomst van de nazi partij. Van Röhm was bekend dat hij homoseksueel was ook al heeft hij dit nooit in het openbaar toegegeven. Omdat Hitler na de machtsovername de SA-top als een obstakel zag voor zijn streven het Duitse leger en leidende industriëlen aan zijn kant te krijgen, gaf hij in juni 1934 de SS opdracht Röhm uit de weg te ruimen. Hij gebruikte Röhm’s homoseksualiteit als legitimatie voor dit eerste bloedbad van het naziregime, de ‘Nacht van de lange messen’, waarbij meer dan honderd mensen (naast vele SA-leiders ook politieke opponenten) werden vermoord.

Het feit dat homoseksuelen ook nazistische overtuigingen konden nahouden heeft bij veel historici het perspectief op de nazistische homovervolging verward. Het fundamentele verschil tussen homoseksueel zijn en homoseksualiteit als stigma werd niet begrijpen. Homoseksuelen zijn, zoals ieder mens, in principe vrij om individuele keuzes te maken. Anders gezegd: ze zijn niet beter of slechter dan andere mensen. Ze zijn ook niet anders dan andere mensen. In de 20de eeuw zijn wij echter dat ze gezien worden als mensen met een stigma, het stigma van de homoseksualiteit. Dit stigma heeft hun leven ook tijdens het nationaalsocialisme veergaand beïnvloedt. Mensen werden vervolgd en tot slachtoffer gemaakt vanwege, niet ondanks hun homoseksualiteit. Daders echter konden binnen de naziehiërarchie opklimmen ondanks, niet vanwege hun homoseksualiteit. Wanneer hun stigma werd ontdekt, werden ook zij tot slachtoffer.

HOE WAS DE SITUATIE VAN LESBISCHE VROUWEN?

De ervaringen van lesbische vrouwen in nazi-Duitsland zijn slechts ten dele te vergelijken met de lotgevallen van homoseksuele mannen. Op deze laatste spitste het vervolgingsbeleid van de nazi’s zich toe. Natuurlijk waren lesbische vrouwen wel degelijk gedwongen ondergronds te gaan. Maar er zijn slechts weinig gevallen bekend van lesbische vrouwen die vanwege hun seksuele voorkeur in een concentratiekamp terechtkwamen.

Onder de naziefunctionarissen keerde tot begin jaren veertig herhaaldelijk de discussie terug of lesbische vrouwen ook vervolgd moesten worden. Drie argumenten prevaleerden uiteindelijk om niet tot systematische vervolging over te gaan. Allereerst was lesbisch zijn in de ogen van de nazi’s zozeer vreemd aan de aard van de Duitse vrouw, dat hiervan weinig gevaar te vrezen was. Daarnaast waren vrouwen in het Derde Rijk uitgesloten van machtsposities, zodat de nazi’s niet beducht hoefden te zijn voor een ‘lesbische samenzwering’ binnen hun gelederen, zoals ze dat wel voor homomannen als een gevaar zagen. Maar het doorslaggevende argument was dat lesbische vrouwen ingezet konden worden voor de vermeerdering van het Arische ras – het ultieme doel van de racistische bevolkingspolitiek van de nazi’s.

VERSCHERPTE VERVOLGING VAN HOMOMANNEN

In 1936 werd de Rijkscentrale ter Bestrijding van Homoseksualiteit en Abortus in het leven geroepen. Hierdoor kreeg de bestrijding van homoseksualiteit een nauwe samenhang met de nationaalsocialistische bevolkingspolitiek en de ideologie van verbetering van het Arische ras.

Vervolging van homoseksuelen vond niet alleen plaats in het Duitse Rijk, waarvan Duitsland en Oostenrijk deel uitmaakten, maar ook in de bezette gebieden die in de toekomst tot dat rijk moesten gaan behoren: Nederland en het bezette deel van Frankrijk, voornamelijk Elsaß–Lothringen. De vervolging van homoseksuelen in andere veroverde landen was, althans theoretisch, van weinig belang binnen de naziebevolkingspolitiek. Zolang er geen Duitsers bij betrokken waren, kwam de zuiverheid van het ‘Arische ras’ immers niet in gevaar. Maar ook in het Duitse Rijk zelf kreeg de vervolging van homoseksuele mannen nooit een even intensief karakter als de Holocaust, de systematische uitroeiing van de Europese joden en de Roma en Sinti.

De meerderheid van de homoseksuelen slaagde erin onzichtbaar te blijven. Niettemin ondergingen alle homoseksuele mannen, bestempeld tot ‘staatsvijanden’, de dreiging van vervolging, marteling en gevangenschap. Net als lesbische vrouwen konden ze alleen in het verborgene uiting geven aan hun gevoelens, hun liefde en vriendschap. Talloze levens zijn door deze voortdurende dreiging beschadigd geraakt.

Volgens schattingen van historici zijn ongeveer honderdduizend mannen op verdenking van homoseksualiteit gearresteerd tijdens het Derde Rijk. De helft van hen werd veroordeeld en belandde in de gevangenis. Ongeveer tien- à vijftienduizend mannen werden na hun tuchthuisstraf gedeporteerd en gevangengezet in concentratiekampen in het Duitse rijk. Een minderheid werd gedeporteerd naar de Duitse vernietigingskampen in Polen. Een gangbare schatting is dat ongeveer zestig procent van de homoseksuelen het kampverblijf niet heeft overleefd.

Na 1945 durfden de overlevenden het niet aan om publiekelijk getuigenis af te leggen van hun ervaringen, uit angst voor vervolging. In West-Duitsland bleef de nazistische wetgeving tegen homoseksualiteit van kracht tot eind jaren zestig. Tot hun grote teleurstelling werden homoseksuele vervolgden na 1945 door de Duitse nog andere regeringen in Europa erkend als slachtoffers van het naziregime.

IS DE HOMOVERVOLGING IN NEDERLAND TIJDENS DE BEZETTING TE VERGELIJKEN MET DE HOMOVERVOLGING IN DUITSLAND?

De Nederlandse homobeweging ontwikkelde zich in de vooroorlogse periode tegen de verdrukking in. Anders dan in Duitsland voor 1933 waren er nauwelijks organisaties, bars of ontmoetingsgelegenheden ontstaan. De politie, de kerken, de overheid hadden bijna iedere poging ertoe weten te verhinderen. In buurland Duitsland lag de situatie veel gunstiger voor de homoseksuele emancipatie, waardoor de Duitse homobeweging als voorbeeld fungeerde. In de jaren dertig verhardde zich ook in Nederland voor de Duitse bezetting het klimaat tegenover homoseksuelen. Na de bezetting kan men in de omgang van de nazi’s met homoseksualiteit een vijftal fases onderkennen zoals eerder in Nazi-Duitsland.

(1) Allereerst moest homoseksualiteit uit de openbaarheid worden teruggedrongen, volgend het Duitse voorbeeld. In Nederland werd dit vooralsnog door de homoseksuele organisaties zelf gedaan. In 1940 hadden Niek Engelschman en Jaap van Leeuwen een tijdschrift opgericht met de strijdvaardige naam Levensrecht, Maandblad voor Vriendschap en Vrijheid. De initiatiefnemers van Levensrecht wisten hoe de nazi’s in Duitsland tegen homoseksualiteit waren opgetreden. De redactie draaide direct na de Duitse inval in mei 1940 de administratie in een wasmachine tot pulp. Wel voerden de Duitsers de grote bibliotheek van Jacob Schorer, de voorman van de naar Duits voorbeeld gemoduleerde homo-emancipatieorganisatie NWHK, af.

(2) In de tweede fase werd de wetgeving in Nederland gelijkgetrokken met die in Duitsland. Sinds 1911 was in Nederland paragraaf 248bis WvS in werking, die seksuele contacten tussen volwassenen en minderjarigen (tussen 16 en 21) van hetzelfde geslacht verbood. Nieuw was de uitbreiding tot alle homoseksuele contacten, dus ook tussen volwassen mannen, en het feit dat ook de minderjarige in een contact strafbaar werd.

(3) De derde fase bestond uit het opzetten van een landelijk registratiesysteem dat opbouwde op politie lijsten van homoseksuelen.

(4) De vierde fase betrof het instellen van een opsporingsapparaat. In oktober 1943 werd een coördinerende inspectie II.D.3 van het Commissariaat Zedendelicten ingesteld bij de Recherchecentrale en analoge instanties bij de plaatselijke afdelingen zedenpolitie.

(5) De vijfde fase had tot de deportatie van Nederlandse homoseksuelen naar concentratiekampen moeten leiden. Maar tot een systematische deportatie kwam het echter niet – niet meer, of nog niet. De Duitse politiechef Rauter klaagde op een gegeven moment zelfs over een gebrekkige inspanning van Nederlandse zijde. Maar was deze klacht wel terecht?

Zoals bij de Jodenvervolging werkte de Nederlandse politie in tegenspraak tot Rauter’s klacht toch loyaal mee aan de opbouw van het instrumentarium voor de homovervolging: de naziewetgeving, de centrale registratie en het gespecialiseerde opsporingsapparaat.

De maatschappij werd rijp gemaakt voor vervolging. Dat het uiteindelijk in het bezette Nederland niet tot een vergelijkbare vervolging is gekomen als in Duitsland ligt waarschijnlijk aan verschillende factoren: de tijdspanne was te kort (in Duitsland lag het hoogtepunt van de homovervolging vier jaar na de machtsovername, tussen 1937-39); de Jodenvervolging had prioriteit; de homobeweging in Nederland zat in die tijd nog te zeer in de kast en was dus moeilijker traceerbaar. En de Nederlandse samenleving, hoe homovijandig ook, wilde niet zonder meer met de Duitsers samenwerken.

Viel de homovervolging in Nederland dus mee? Een medewerker van het NOS-journaal bracht dit in een gesprek met mij op het punt: ‘zonder massale Nederlandse homoseksuele slachtoffers in de kampen kunnen wij geen aandacht aan de homovervolging geven.’

In de statistieke omgang met slachtoffergetallen verdwijnt de empathie met de individuele slachtoffers. De structurele verscherpingen in de wetgeving en het politie- en justitieapparaat tijdens de bezetting worden genegeerd, de gevolgen blijven onbesproken: de veergaande rechtsonzekerheid, de alledaagse vervolgingsdreiging en de maatschappelijke minachting.

Het maatschappelijke klimaat in Nederland rondom homoseksualiteit was inderdaad uitgesproken negatief niet alleen tijdens, maar ook voor en na de bezetting. De in de tentoonstelling besproken ‘homospecialist’ bij de Amsterdamse politie, de brigadier Jasper van Opijnen, belichaamt deze continuïteit; hij was werkzaam bij de Amsterdamse zedenpolitie sinds 1920. Van Opijnen had menig homoseksueel gearresteerd. Waaronder ook Joodse homoseksuelen die dan vervolgens aan de Duitsers werden uitgeleverd en in Auschwitz vergast werden. In 1946 bij zijn pensionering maakten zijn collega’s zelfs grappen over zijn dienstijver als ‘Homoführer’. Zijn collaboratie werd een anekdote in een lollige afscheidspartij.

O zijn kennis op dat gebied

Vindt zijn weerga niet.

Hij heeft toch duizenden ‘Mietjes’ ontpopt

In onze ad-mi-ni-stra-tie gestopt.

Wij zullen zeker nog langen tijd

Missen zijn ‘keurig’ beleid.

Hij was Homoführer. Hij was in één woord

Eenig in zijn soort.

ERFGOED EN HOMOSEKSUALITEIT

“Wat voor de één een anekdote is, is voor de ander bittere realiteit. Hoeveel anekdotes hebben we nodig?”, vroeg Ayaan Hirsi Ali bij de opening van de tentoonstelling Wie kan ik nog vertrouwen? in Westerbork op 21 april. Haar vraag raakt de kern van de tentoonstelling, maar ook de kern van de geschiedschrijving rond het thema homovervolging. Hoe wordt uit een anekdote, interessant voor een moment, een verhaal dat wij het waard vinden om te vertellen en te bewaren? En hoe kunnen wij via deze verhalen tot een oordeel komen over het verleden en over het heden?

De tentoonstelling Wie kan ik nog vertrouwen? is vanaf 21 september te zien, hier in het verzetsmuseum. Zij toont het leven van lesbische vrouwen en homoseksuele mannen in Duitsland en Nederland tussen 1933 en 1945, met als zwaartepunt hun vervolging en verzet. Het is de eerste keer voor Nederland dat deze ‘zwarte bladzijde van de homogeschiedenis’ zo duidelijk op de kaart wordt gezet in een expositie.

De tentoonstelling laat zien hoe het individu in een totalitaire staat onder druk komt te staan en hoe een medeplichtige maatschappij verregaand bijdraagt aan deze druk. De reductie van het individu tot een categorie, in dit geval tot de categorie ‘homoseksueel’, is het uitgangspunt van een totalitaire staat en van totalitaire denkbeelden – toen en nu.

De blik van de dader, waar de vervolgden alleen nog als minderwaardig of levensonwaardig verschenen, werd in de tentoonstelling door de focus op het individu haast vanzelf tot thema. Homoseksuelen hebben zoals iedereen familie, vrienden, collega’s, buren: hoe reageerden die op hun bedreiging? De verhalen in de tentoonstelling laten zien dat mensen ook in een dictatuur keuzes hebben en maken. De tentoonstelling legt de gevolgen ervan voor aan de bezoeker: wie kan ik nog vertrouwen in een dictatuur waar ik als minderwaardig wordt gezien? Waarom steunt mij de één, en verraadt mij de ander?

Bij het maken van deze tentoonstelling viel mij opnieuw op hoe schaars het materiaal is. Over de homogeschiedenis in de 20ste eeuw, zowel de zwarte bladzijden als de successen vanaf de jaren zestig, is nauwelijks iets terug te vinden in Nederlandse musea of archieven. Ik kon vooral terecht bij private bronnen, zoals particuliere archieven en het IHLIA (Internationaal Homo/Lesbisch Informatiecentrum en Archief) voor foto’s, objecten en correspondenties. Zij proberen te redden en te bewaren, maar vanwege hun zeer beperkte middelen is dit vaak tevergeefs. Het gros van documenten, foto’s en objecten uit de 20ste eeuw waarmee het leven van homoseksuelen gedocumenteerd zou kunnen worden, belandt op de vuilnis.

Terwijl de Nederlandse samenleving sinds de jaren zestig vergaand is veranderd en als een van de weinigen landen gelijke rechten voor homoseksuelen heeft geregeld, gaan de erfgoedinstellingen door alsof er niets is gebeurd. Wij danken het aan de bereidheid van het herinneringscentrum Westerbork, de verzetsmusea in Amsterdam en Leeuwaarden en het Nationaal monument kamp Vught dat wij deze tentoonstelling in hun instellingen kunnen presenteren. Maar binnen de erfgoedinstellingen is dit een uitzondering: homoseksualiteit blijft in musea en archieven als vanouds onzichtbaar. Dont’ ask, don’t tell, don’t preserve.

In vergelijking met andere media – televisie, film, literatuur of theater – waarin homoseksualiteit al lang vanzelfsprekend deel uitmaakt lopen musea en archieven achter. Ze hebben hun collectie zelden vanuit dit perspectief bekeken. Er wordt niet doelgericht verzameld. Men kan dan ook vaak geen expertise bieden. Terwijl musea wel, en terecht, een doelgericht beleid tegenover nieuwe bezoekers uit migranten gemeenschappen ontwikkelen, ontbreken vergelijkbare initiatieven bij dit thema.

Dit gebrek heeft verschillende redenen. Homoseksualiteit wordt nog steeds gereduceerd tot een geschiedenis van seksualiteit en identiteit. Terwijl het bestudeerd zou moeten worden als deel van een complexe sociale geschiedenis. Niet hun seksuele gedrag kenmerkte het leven van lesbische vrouwen en homoseksuele mannen in de twintigste eeuw. Hun leven werd bepaald door de maatschappelijke, medische, juridische en symbolische uitsluiting door de samenleving.

Homogeschiedenis is dus Nederlandse geschiedenis tot in de haarvaten. Samenlevingen definiëren zich door grenzen te trekken, daadwerkelijk en symbolisch: ‘homoseksualiteit’ functioneerde lange tijd als een symbolische grens voor het construct van normaliteit.

Een samenleving definieert zich ook door wat ze bewaart en koestert. Het collectieve geheugen werkt als een filter. Waar komen wij vandaan, hoe zijn we zo geworden, waar gaan wij naartoe? Erfgoedinstellingen helpen de beslissingen die wij in het verleden hebben genomen te bewaren en te verduidelijken voor komende generaties. Gebrek aan historische kennis en voorstellingsvermogen kan zich al snel vertalen in onverschilligheid. Zoals dit schrijnend werd getoond door het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken wanneer het constateerde dat het voor homoseksuelen in Iran ´niet totaal onmogelijk is om op maatschappelijk en sociaal gebied te functioneren´ mits ze ´niet al te openlijk voor de seksuele geaardheid uitkomen`. Ook onze minister president liet zien dat hij in het buitenland onze normen en waarden, zoals de openstelling van het huwelijk voor homoseksuele mannen en vrouwen, niet zonder meer verdedigt. Balkenende had in Indonesië ook kunnen kiezen voor een reactie in de geest van de Spaanse premier Zapatero. Die toonde aanmerkelijk meer oog voor de historische stap die werd gezet door de openstelling van het huwelijk voor homoseksuelen in Spanje: ´Wij maken deze wet niet voor mensen die ver weg zijn en onbekend. We verruimen de mogelijkheid van geluk voor onze buren, onze collega’s, onze vrienden en onze families. En tegelijkertijd scheppen wij een beschaafdere samenleving omdat een beschaafdere samenleving zijn leden niet vernedert.´

Het is tijd voor een duidelijk beleidsplan dat erfgoedinstellingen stimuleert ook dit aspect van de Nederlandse geschiedenis te documenteren. Daarbij hoort, zoals bij andere doelgroepen ook, een directe communicatie vanuit de erfgoedsector. De discussie in de laatste jaren over een homomuseum binnen de Nederlandse museumwereld eindigde echter, voordat ze begon, vaak met een gemakkelijke ridiculisering. Het is geen thema voor museaal Nederland. Maar ook homo Nederland zelf moet zich daadkrachtiger inspannen.

Homoseksuelen en heteroseksuelen hebben samen een unieke ontwikkeling meegemaakt in de laatste eeuw, tenminste hier, in dit land. Deze verworvenheid moet deel van ons nationaal geheugen worden. Komende generaties hebben een recht erop dat dit deel van hun geschiedenis op een vanzelfsprekende manier wordt bewaard.

VERTROUWEN

Ik wil afsluiten met een reflectie over de centrale vraag van de tentoonstelling: wie kan ik nog vertrouwen? Iedere tentoonstelling ook al gaat zij over het verleden is ontwikkeld vanuit een heden. Tijdens het maken van de tentoonstelling werd die distantie tussen het verleden en het heden een centrale vraag.

Met de ondergang van de nationaalsocialistische staat zijn diens totalitaire opvattingen niet verdwenen. In een grote hoeveelheid staten worden homoseksuelen vandaag vervolgd, gevoed door fascistische, communistische of religieusfundamentalistische regimes. De locaties zijn verandert, totalitair en racistisch gedachtegoed is gebleven. Ook democratische staten hebben problemen met groeiende fundamentalistische stromingen van christelijke, joodse, islamitische of indoesignatuur en met neofascistische ideologieën.

Twee weken geleden werd in Rusland de eerste gay pride manifestatie met bruut geweld aangevallen door orthodoxe, extreem nationalistische en fascistische groepen. De politie keek toe. Rusland – op dit moment voorzitter van de Raad van Europa – weigert homoseksuelen het recht op vergadering en vrije meningsuiting, desnoods met straatterreur. Terwijl het antidiscriminatiebeleid van de Europese Unie grote vooruitgang heeft geboekt bij de gelijkstelling van homoseksuelen in West- en Noord-Europa, verscherpen bijvoorbeeld de tegenwoordige Letlandse en Poolse regeringen hun inspanning homoseksuelen van Europese grondrechten uit te sluiten. De Poolse president Lech Kaczynski beroept zich op christelijke waarden in zijn haatcampagne tegen homoseksuelen. Ook in andere landen wordt religie misbruikt als veilig platvorm voor de verkondiging van haat en geweld tegen homoseksuelen. Zo riep de Irakese sjiitische ayatollah Ali al-Sistani in maart van dit jaar ertoe op homoseksuelen “op de meest gruwelijke wijze” te vermoorden, de Russische Grootmoefti Talgat Tadzhuddin vindt het een uitdrukking van geloof homoseksuelen in elkaar te slaan.

De terugkeer van transnationaal opererende religies in het openbaar leven en hun veelvoudig gebrek aan respect voor andere levensaanschouwingen zet ook de discussie in Nederland op scherp. Delen van islamitische migranten gemeenschappen bekrachtigen hun afwijzing van homoseksualiteit die zij uit hun eigen cultuur kennen. Het web en andere media geven niet alleen een platform voor de strijd voor homorechten, maar ook voor de verspreiding voor homofobie hier.

Homoseksuelen hebben in Nederland een lange strijd gevoerd om zich niet te moeten verbergen en zichtbaar en met respect hun leven te kunnen leiden. De gouden jaren van onbezorgdheid lijken echter voorbij. Ik heb deze onbezorgdheid van Nederlandse homoseksuelen altijd als historisch uniek en een groot goed ervaren. Het verlies aan vertrouwen in een veilige omgeving is een pijnlijke stap terug.