Please find photos and speech also here:

Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, liebe Freundinnen und Freunde,

Danke für die Einladung! Berlin hat viele Denkmäler, aber nur eines davon integriert eine Filmsequenz: Das auf dem Entwurf von Michael Elmgreen und Ingar Dragset basierende und 2008 eingeweihte Denkmal für die im Nationalsozialismus verfolgten Homosexuellen. In unmittelbarer Nähe zum Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas zitiert es dessen architektonische Sprache der Stelen.

Wenn man abends dort läuft, zwischen Brandenburger Tor und Potsdamer Platz, überrascht das Licht der im Denkmal projizierten Filmbilder. Was gibt es dort zu sehen? Man muss sich an ein schmales Glasfenster stellen, das in die Außenwand des Denkmals eingelassen ist: jeweils nur eine Besucherin kann nach innen schauen. Gezeigt wird eine Endlosschleife von zwei sich küssenden jungen Männern.

Der Kuss als visuelles Thema soll an die NS-Zeit erinnern, in der ein Kuss zwischen zwei Männern als strafbar gewertet werden und vielleicht zu Verhaftung, Gefängnis, oder gar einer Einweisung in ein KZ führen konnte. Ein Einführungstext vor dem Denkmal erklärt diesen Zusammenhang.

Der Film selbst vermeidet historische Assoziationen: wir sehen einen Kuss im Hier und Jetzt von Berlin. Wann haben Sie zum letzten Mal den Kuss zwischen einem Mann und einer Frau bewusst als solchen wahrgenommen? Sich dazu in Bezug gesetzt? Über Öffentlichkeit nachgedacht?

Die filmische Inszenierung konfrontiert mit der unbequemen Einsicht, dass das Bild zwei sich küssender Männer zu Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts eine Erfahrung bestimmter Art konstruiert. Wieso ist das so? Was sehen wir da? In diesem Kuss? Das Denkmal wurde seit 2008 dreimal beschädigt.

Während die historische Referenz des Kusses – als ikonographischer shortcut – nachzuvollziehen ist, öffnet sich die Denkmalarchitektur einer problematischen Ambivalenz des Schauens: Sie führt den Besucher in eine voyeuristische Betrachterposition. Die Küssenden werden zum Objekt. Nun ist dies eine reale Erfahrung für Homosexuelle, dass Zuneigung, ausgedrückt in der Öffentlichkeit, in einem Gespräch, einer Umarmung oder eben einem Kuss, zu diesem Blick von außen führt.

Die architektonisch geleitete Wahrnehmung durch das Fenster repliziert die prinzipielle politische wie visuelle Wahrnehmung homosexuellen Lebens im 20. Jahrhundert. Sie zeigt Homosexualität in eben jener Figur, in der sie eingeschlossen war – dem Gestus des Zurschaugestelltseins. Diese Grenzziehung führte letztlich zu Diskriminierung und Verfolgung.

Die Filmsequenz löste eine öffentliche Diskussion aus, in dem der mannmännliche Kuss als Ausschluss weiblicher Homosexualität angegriffen wurde. Die Bundesregierung hat dem Denkmal eine Doppelfunktion gegeben, das in seiner Reichweite überaus fordernd ist: als Denkmal die NS-Verfolgung männlicher Homosexualität zu erinnern und gleichzeitig ein beständiges Zeichen zu setzen gegen die fortwährende Diskriminierung homosexueller Männer und Frauen heute.

Im Juni 2007 entschied die Bundesregierung, mit Zustimmung der Künstler, eine Fortentwicklung der Denkmalkonzeption durch einen jeweils zweijährigen Film Wettbewerb. Welch ungewöhnliche und wunderbare Chance: Das Denkmal verhärtet sich nicht als zu Stein gewordene Erinnerung. Stein ist hier sozusagen nur eine Hülle für Bilder, die wir projizieren wollen. Gedenkzeichen an homosexuelle Verfolgung stießen lange auf starken gesellschaftlichen Widerstand. Der Wettbewerb ermöglicht eine notwendige Diskussion: Für wen, warum, mit welchem Ziel, in welcher Form versuchen wir, an die historische Verfolgung zu erinnern und ein Zeichen gegen Diskriminierung heute zu setzen? Ist die NS-Verfolgung ein extremer Ausdruck von Homophobie oder eine singuläre Ausnahme in einer Geschichte relativer Intoleranz? Was erschließt, was verschließt sich durch den Vergleich des Schicksals der Männer mit dem rosa Winkel mit dem lesbischer Frauen im Nationalsozialismus?

Die durch die historische Forschung dokumentierte Differenz findet breiten Konsens bei Lesben und Schwulen. Doch zu Recht wird auf die Strafbarkeit weiblicher Homosexualität in Österreich und auf Einzelfälle verfolgter lesbischer Frauen verwiesen und die Frage gestellt, wie die prekäre Lebenssituation lesbischer Frauen im dritten Reich – nach der Zerschlagung der lesbischen Kultur der zwanziger Jahre – in unserer Gedenkkultur angemessen thematisiert werden kann. Lesbische Frauen, die ins Visier der Kriminalpolizei gerieten, erfuhren die Verachtung seitens der staatlichen Behörden und ein gesellschaftliches Klima der Rechtlosigkeit; nur die Geringschätzung lesbischer Sexualität veranlasste das NS-Regime, diese nicht unter Strafe zu stellen. Die Diskussion, die sich an dem Erstlingsfilm entzündete – emotional, kontrovers, und konzentriert nach Antworten suchend – bedeutete einen wichtigen Zugewinn, in dem sie diese Fragen ernst nahm.

Wird die historische Erinnerungsfunktion des Denkmals durch den stark hervorgehobenen Gegenwartsbezug potentiell geschwächt?

Die Zeit, und der öffentliche Umgang mit dem Denkmal, unser Umgang wird das zeigen. Für die Überlebenden der Homosexuellenverfolgung kam die Anerkennung zu spät. Sie lebten und starben allein mit ihren Erinnerungen. Welchen Film wir auch wählen – ihnen sind wir Gedenken schuldig, in immer wieder neu zu findenden Ausdrucksformen. Das Denkmal kann hier nur einen Beitrag leisten.

Unser Gedenken kann sich weder von der Vergangenheit verabschieden, noch sich in ihr einschließen. “A memorial unresponsive to the future would violate the memory of the past.”: Ein Denkmal, das auf die Zukunft nicht reagiert, verletzt die Erinnerung an die Vergangenheit, so fasst Elie Wiesel den Zusammenhang von Gedenken und Verantwortung zusammen. Mit dem Untergang des NS-Staates sind dessen totalitären homophoben Auffassungen nicht verschwunden. In Europa haben Homosexuelle zunehmend ähnliche Rechte wie Heterosexuelle. Doch in vielen Staaten werden sie von Grundrechten ausgeschlossen und verfolgt. Religionen werden als Plattform für Intoleranz, gar Hass missbraucht.

„Aus seiner Geschichte heraus hat Deutschland eine besondere Verantwortung, Menschenrechtsverletzungen gegenüber Schwulen und Lesben entschieden entgegenzutreten“, so die Gedenktafel vor dem Denkmal. Die Selbstverpflichtung der Bundesregierung ist eine entschiedene Aussage. Wir können ihr nur nachkommen, wenn wir – über Landesgrenzen hinweg – die menschenverachtende Propaganda gegen Homosexualität benennen und bekämpfen: ob in Uganda, Malawi, Iran, Russland oder dem Vatikan. Hier entscheidet sich, ob Gedenken selbstbezüglich bleibt oder aus ihm Verantwortung erwächst.

Der gewinnende Film des Wettbewerbs 2011 ist eine Produktion von Gerald Backhaus, Bernd Fischer und Ibrahim Gülnar, und ich gratuliere schon einmal ganz herzlich.

Der Film spielt ganz erkennbar im Berlin von heute und zeigt, der Vorgabe entsprechend, Küsse von Männer- und Frauenpaaren; Vignetten des Alltags, dokumentarisch inszeniert, erkennbar. Für seine zentrale Aussage jedoch ist dies sekundär. Die Endlosschleife schlägt dem Besucher einen anderen Blick vor: den Blick auf sich selbst. Der Film bricht die voyeuristische Festschreibung der Zuschauerin: Die Kamera zoomt immer wieder aus und zeigt stattdessen den konstitutiven Blick der Mehrheitsgesellschaft auf den homosexuellen Kuss – den Blick eines Kindes, eines Nachbarn, einer Passantin, in einer Bar, im Stadium. Es sind ganz unterschiedliche Blicke.

Während man als Besucher diesen projizierten Kuss, diese intime selbstvergessene Geste wahrnimmt, sieht man sich nunmehr auch immer selbst als Beobachtenden – in diesem Blick von außen, in diesem Eingriff in die Intimität eines Paares. Der Film öffnet uns die Augen vor allem für unseren eigenen Blick auf das vermeintlich Andere.[1]

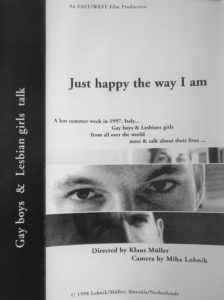

[1]Zu einer ausführlichen Auseinandersetzung mit filmischen Visualisierungen der NS-Homosexuellen-Verfolgung siehe: Klaus Müller, Zwischen Denunziation und Erinnerung. Filmische Visualisierungen der NS-Homosexuellenverfolgung, in: Claudia Bruns mit Asal Dardan/Anette Dietrich (Hrsg.), „Welchen der Steine du hebst.“ Filmische Erinnerung an den Holocaust, Berlin 2011. Eine bibliographische Übersicht zur Forschung über die NS-Verfolgung männlicher und weiblicher Homosexualität im Nationalsozialismus, auf die ich mich hier beziehe, findet sich in meinem Aussatz: Klaus Müller, Gedenken und Verachtung: Zum gesellschaftlichen Umgang mit der nationalsozialistischen Homosexuellenverfolgung, in: Insa Eschebach (Hg.), Homophobie, Devianz und weibliche Homosexualität im Nationalsozialismus. Geschichte und Gedenken. Schriftenreihe der Stiftung Brandenburgische Gedenkstätten, Berlin 2011.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCE SPEECH

Rede Dr. Klaus Mueller, Neuer Film im Denkmal für die im Nationalsozialismus verfolgten Homosexuellen, Übergabe an die Öffentlichkeit, Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas, Donnerstag, 26. Januar 2012